In this week’s newsletter, we talk about Indian companies directly listing on foreign stock exchanges, the Global South and money tips.

If you’d like to receive our 3-min daily newsletter that breaks down the world of business & finance in plain English – click here. Or, download the Finshots app here.

Indian companies get a foreign stock exchange visa

Companies that go public, do so because they get larger access to capital. It helps them expand their business, launch new products or cut down debt. Most businesses in India tap into the Indian equity markets. However, if they were allowed to step outside and list on foreign stock exchanges, they could raise even more money.

But unfortunately, Indian laws don’t allow companies incorporated here to do that. Granted, there are Indian companies that have listed overseas in the past. There’s Infosys, Tata Motors, HDFC Bank, MakeMyTrip and many others. But they did so using something called Depositary Receipts (DRs).

Simply put, an Indian company that wants to list overseas sells its shares to a local bank. It could be the Stock Holding Corporation of India, HDFC Bank or ICICI Bank. These banks keep the shares safe in their custody. Meanwhile, there’s another intermediary called a depositary bank overseas which works with the Indian bank by putting together an arrangement. For every 10 shares held by the Indian bank, they create and issue a new share (called a depository receipt or DR). The receipt derives its value from underlying shares in India. This example assumes that 10 shares represent 1 DR. But that ratio could change. Anyway, once the overseas bank issues these DRs, foreign investors can buy and sell them on a foreign stock exchange using their local currency. So effectively, they can lay their hands on the Indian company’s stock.

So when Infosys floated its shares on the New York Stock Exchange it used American Depositary Receipts (ADRs). Likewise, if a company wants to list its shares in other global markets it can use Global Depositary Receipts (GDRs).

But soon, that may not be necessary at least for select Indian companies. Because a couple of days ago, the government gave effect to an amendment it made to the Companies Act in 2020. It said that certain companies could go the direct route and list on foreign stock exchanges. Okay, but what’s wrong with going the GDR way, you ask?

To begin with, companies could not take this route if they weren’t listed on the Indian stock exchanges in the first place. So they’d have to get the necessary clearance to float their shares to the Indian public. Then, they’d have to spend more time and money to float their shares overseas through an intermediary. It was a time-consuming and costly affair.

Foreign investors also preferred investing directly since DRs are traded in their local currency. It exposed them to a currency fluctuation risk. This means that an Indian company’s GDR could be valued differently in the US and European markets despite being associated with the same company.

Of course, the government and market regulator SEBI (Securities and Exchange Board of India) understood this and floated simpler rules for DRs in 2014. Unlisted companies could use them to tap overseas financial markets. Even if companies didn’t choose to raise capital overseas, a foreign depositary could still issue DRs for its shares if there was a lot of demand from investors. It’s called an unsponsored DR. The depositary would have to be a broker cum dealer who’d hold the Indian company’s shares.

But these rules didn’t really take off even until a couple of years later. And the ambiguity led to a drop in ADR and GDR issues. Between 2008 and 2018 Indian companies issued over 100 ADRs and GDRs in foreign markets. But since then, there have been no issues at all.

So why weren’t the new DR rules implemented faster then?

Well, regulators were worried about companies using DRs to launder money. You could blame it on a huge GDR manipulation scam worth over $150 million since 2010. Arun Panchariya, the man at the epicentre of this fraudulent scheme used interrelated companies to round trip shares floated via GDRs back to India, pocketing crores of Rupees. Basically, he and his associates pushed companies to create an artificial demand for their GDRs.

And they misused one GDR trait we didn’t tell you about earlier. Foreign investors can surrender their GDRs in exchange for shares. Once they have these shares in their kitty, they can sell them to Indian investors. That’s exactly what foreign investors did in the Panchariya scam. They offloaded their shares to a common bunch of investors who traded the stocks among themselves first. That would artificially inflate stock prices before selling them to innocent retail investors.

That explains why the government has been skeptical about the new DR rules. However, with a set of amendments in 2020 and some additional rules to keep a watchful eye on money laundering, the government hoped to fix this issue once and for all. And these rules finally took off a couple of days ago.

Will this make it easy for Indian companies to raise money overseas?

Well, the government still needs to clear the air over a lot of nitty-gritty details that the market is still unsure about. But it’s definitely a start.

What’s this Global South, anyway?

Every second headline today seems to have the phrase “Global South”.

Here’s one in the HinduBusinessline on Monday: “India’s G20 Presidency strove to mainstream the concerns and aspirations of the Global South, says FM Sitharaman”

Time published this five days ago: “The West Is Losing the Global South Over Gaza”

And here’s another from The Economist from three weeks ago: “Xi Jinping wants to be loved by the global south”

Everyone’s talking about the ‘Global South’ and it will probably end up being the geopolitical phrase of this decade. So we thought, why not delve into what exactly this Global South means? And why is the term gaining so much prominence today?

Well, the origin of the term itself comes from quite unexpected quarters. In the 1960s, the US was in war in Vietnam. It wasn’t America’s war to begin with but they waded in because they were afraid a Communist regime was shaping up in the region. Not just in Vietnam but its neighbours too. Naturally, a lot of Americans weren’t pleased with the war. Especially the left-leaning folks. And in 1969, Carl Oglesby, a writer and a political activist, penned a column which gave birth to the term. He wrote, “the North’s dominance over the global South . . . [has] converged . . . to produce an intolerable social order.” He was referring to how certain countries were lording over others to create a world order that suited them.

But who’s the North and who’s the South, you ask?

Let’s think about it this way. Take a map and imagine how the world economic order looked like a few decades ago. Where are the richer countries with a higher standard of living? And where are the poorer regions that probably suffer from higher rates of poverty and hunger?

Now try and draw a line trying to divide the countries into the haves and have-nots. You will probably find that your line buckets most of the well-to-do nations in the Northern Hemisphere and the others in the Southern Hemisphere. Well, that’s the North-South divide. And we told you to draw a line for a reason. Because that’s exactly what a former West German chancellor named Willy Brandt did in the 1980s. He drew a similar line for a report he was writing on international affairs. And it came to be called the Brandt Line.

Of course, you could argue that this was a lazy categorization since relatively poorer Eastern European regions were in the North and countries like Australia and New Zealand were in the South. But the Brandt line was quite curvaceous that way. Take a look at the cover image of the story again.

And it was an easy categorisation nonetheless. A simple thumb rule that everyone could understand. So while Oglesby might’ve coined it, it’s Brandt’s Line which brought it into geography books.

But even then, the term didn’t immediately catch on. Economic pundits and political commentators weren’t using it. The media didn’t carry headlines with this phrase either. And that’s because, for a long time, there was another phrase to describe the poorer countries — the “Third World”. Now initially, there was nothing negative about the Third World. It was just a way to split the world into 3 bits. The First World was the superpower US and its Western Allies. The Second World was the other superpower Soviet Union and its communist friends. And the Third World was simply other nations who didn’t want to side with either of these two power blocs. But after the Soviet Union collapsed, people in the West began to use the Third World in quite a derogatory manner. To try and imply that this set of countries suffered from poverty, corrupt governments, and a poor quality of life. Soon, the term began to be considered a pejorative.

So there emerged another phrase — ‘developing countries’.

This doesn’t seem too bad, does it? It simply denoted that they were a group of countries that were striving to reach the next economic strata. And initially, everyone was happy with this term. But then, people began to point out that it created a hierarchy among countries. That this implied one country was better than the others based on some vanity metric.

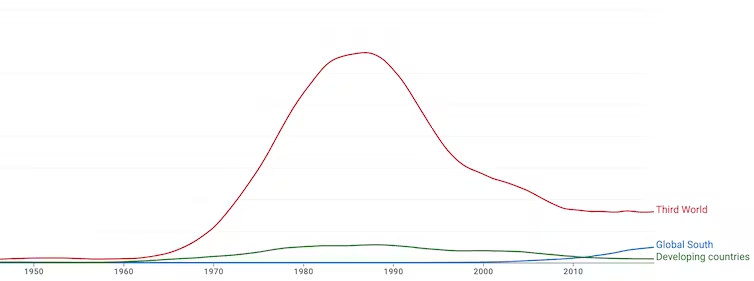

So we had to find a new term again. And in the 2010s, the term Global South slowly began to catch on again. And you can see in the chart how the usage of the terms ‘Global South,’ Third World,‘ and ‘Developing countries’ in English language sources have changed over the past few decades.

Source: The Conversation

So who’s part of this Global South now, you ask?

Well, the first thing to remember is that it isn’t really an organisation. It’s just a grouping. So some folks simply look at the members of the G77 to determine who’s part of this. It’s a coalition of countries at the United Nations which now has 134 members — including India, China, and Nigeria. These are what you’d call the “developing” countries. And this group has taken to calling themselves the Global South.

That’s the group that India wooed with its “Voice of Global South” Summit earlier this year too.

Now experts say that there are a few reasons why these countries have been joining hands.

For starters, there’s the colonial hangover. Most of these countries have a shared history of European colonial rule. They’ve been beaten down in the past. They’ve been stripped of their resources and reduced to poverty. So there’s a mutual feeling of being oppressed.

And this oppression has continued in some form or another on the international stage too. They haven’t been given sufficient representation in international institutions. Whenever they’ve had to borrow money from international entities, it has come with a long list of strings attached. And this has made them even more vulnerable. For instance, 95% of Nigeria’s revenues go towards repaying all its debt. And many other countries are struggling too.

Then there’s the more recent problem of climate change. See, developed countries have gone through their industrialization phase. They’ve emitted all the harmful gases they could to get ahead in the world. Just look at the data between 1751 and 2017 — a whopping 47% of the CO2 emissions came from the US, EU and the UK. Africa and South America put together only accounted for 6%! But now that it’s time for the developing countries to grow faster and increase energy consumption in the process, the West wants to sound the alarm and ask everyone else to reduce emissions.

Also, when the pandemic ravaged the world, the rich countries were busy providing booster doses for their citizens even as the WHO urged them to give priority to countries which didn’t even have access to the vaccines. It created an even bigger sense of inequality.

And most recently, look at the war in Ukraine. The West pledged $170 billion in aid to Ukraine in the first year of the year. This was almost as much as the entire global aid package in 2021. So it simply created a situation in which the poorer countries were led to believe that rich countries would donate but only if it was in their interest.

Slowly, these countries have become tired of toeing the line of the West. They banded together to stand up for themselves against the Western hegemony. Just look at how India recently pushed for the introduction of the African Union into the G20 league. They’re pushing for a seat at the table.

And they’ve wholeheartedly embraced the ‘Global South’ terminology to signify that. Because as former Chilean Ambassador Jorge Hein wrote: “…whereas the terms “Third World” and “underdeveloped” convey images of economic powerlessness, that isn’t true of the “Global South.”

Now we just have to wait and see how this Global South can further push their economic and trade agenda on the world stage.

Money Tips : The risk of not investing

: The risk of not investing

When you hear the word risk in an investing context what’s the first thing that pops into your head?

I’d assume it’s something to do with losing money.

Imagine a scenario where you’ve invested your money in stocks or mutual funds. Then there’s a market crash and you lose it all. You can already hear your heart beat louder in this imagined reality. You don’t want to stomach this kind of risk. So you decide to simply stick to safe investments. Like FDs.

After all, you know that the magic of compounding works in almost any kind of investment. Whether it’s the humble fixed deposit or the hallowed mutual fund.

But what if I told you there’s another type of risk?

It’s not the risk of losing money. It’s the risk of not meeting your goals.

You see, an FD is safe. The money lies with your bank and as long as it’s one of good repute, you don’t really have to worry about it going bankrupt and swallowing your money. But because it’s considered to be relatively safe, you can’t expect very high returns either. It barely keeps up with inflation. And then there’s the tax you have to pay on interest as well. So it may not be the best choice to grow money. Or build wealth.

The only way you can meet your goals is if you stay on the hamster wheel — work hard, earn more, save more. And then use those savings.

But what if you invest your money sensibly?

You take on some amount of risk that helps you get to your goals. You invest in stocks or mutual funds that might seem risky on the face of it. But over a long period of time, it rewards you for your patience. You beat inflation and then some.

Because remember, at some point in life, your income will end. But your expenses continue. Investing in assets that can build long-term wealth for you is the only real way to meet those expenses. Not doing so is what’s risky.

And that’s all for today folks! If you learned something new, make sure to subscribe to Finshots for more such insights 🙂

Finshots is now on WhatsApp Channels. Click here to follow us and get your daily financial fix in just 3 minutes.

Finshots is now on WhatsApp Channels. Click here to follow us and get your daily financial fix in just 3 minutes.