Introduction

If 2020 was the year of the coronavirus pandemic, then 2021 is shaping up to be the year of the vaccine. And although there is reason to be optimistic about the arrival of coronavirus vaccines, there are significant barriers to vaccine availability and access in many parts of the world. As the global vaccination drive gains traction, familiar patterns of global inequity are resurfacing.

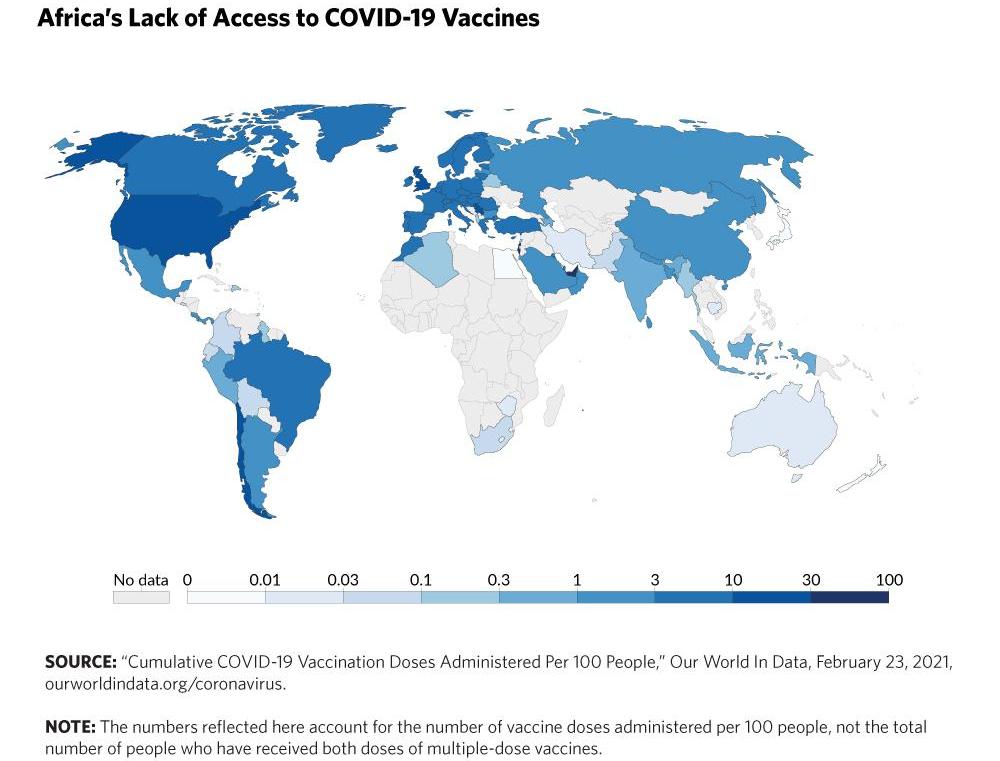

Poorer and less powerful countries, particularly those in Africa, are faced with barriers to vaccine access that pose a serious threat to their chances of a smooth post-pandemic recovery.

Surveying the Economic Damage

The pandemic has severely disrupted economic activity across Africa, as it has in other regions.

Not only did Africa’s two largest economies, Nigeria and South Africa, succumb to recession in 2020, but hopes for recovery will be dashed until 2022.

Exports have been hampered by weakening demand in advanced economies, and the tourism and hospitality industries in the small island nations have been disrupted by travel restrictions. Small businesses have been impacted by strict lock-downs since the beginning of the pandemic. Migrant remittances to African countries, which now outweigh aid and foreign direct investment, dropped by 9%. There is a slew of other issues as well. Debt servicing, like in other parts of the world, limits the ability of even the most well-intentioned African governments to provide social assistance, stimulate the economy, and procure medical supplies.

For the foreseeable future, most African economies will continue to suffer from pandemic-related hardship and longer-term repercussions could also be devastating.

When will African countries be able to get enough vaccines to start the long process of economic recovery?

According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, vaccine access for healthcare workers, the elderly, and other vulnerable groups will not be available in Africa until 2023 at the earliest. As a result, the continent may suffer greatly from the pandemic’s socioeconomic impacts due to vaccine access challenges.

Another major issue is the cost of procuring and delivering these vaccines. According to the African Union’s vaccine strategy, procuring and delivering the 1.5 billion doses required will cost around $9 billion. While the African Export-Import Bank has guaranteed a $2 billion loan, this will still add to the financial burden on countries that are already struggling with public debt. And even if vaccine supplies are secured, infrastructural and logistical challenges will impede COVID-19 vaccine delivery in Africa. Other issues include a shortage of healthcare workers, and a widespread misunderstanding about the COVID-19 vaccine.

The Impact of Geopolitics

Africa’s difficulties in obtaining COVID-19 vaccines are exacerbated by a deteriorating multilateral order marked by rising great power rivalries. African countries, like much of the developing world, are caught between China’s soft power diplomacy and the West’s vaccine nationalism.

CHINA’S VACCINE DIPLOMACY

In the push for vaccine diplomacy, China has positioned itself as a benign power assisting other developing countries in combating a pandemic, and as a result, China’s President Xi Jinping pledged in May 2020 to make China’s COVID-19 vaccines a “global public good”.

Unsurprisingly, the specifics of vaccine delivery remain a mystery. For example, the Chinese government initially stated that it would provide these vaccines free of charge to African countries, but later clarified that it would provide low-cost access. There are also concerns about the efficacy of these vaccines, as there were concerns about the quality of some medical supplies donated by Chinese entities in the early days of the pandemic.

OTHER COUNTRIES

Other non-Western countries are stepping up their vaccine diplomacy as well. Russia has offered the African Union 300 million doses of its Sputnik V vaccine, as well as a financial package to help countries obtain the vaccine. India is also extending its soft power by utilizing its vast pharmaceutical industry. The Serum Institute of India, the world’s largest vaccine factory, provided free Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine doses to Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, the Maldives, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Seychelles.

THE ROLE OF VACCINE NATIONALISM

This soft power diplomacy by rising powers coexists with wealthy countries’ vaccine nationalism.

A trend of hoarding limited medical supplies has been brought to attention by prominent global public health leaders, to the detriment of the vast majority of countries around the world.

Canada, for example, has purchased nearly nine times the amount of vaccines required to protect its entire population. Similarly, the EU, as well as the UK and the US, have purchased more than three times their population’s vaccine needs.

On one level, it’s understandable that countries that have spent billions of dollars in taxpayer funds on vaccine research and development should be first in line. What is inexcusable, however, is that vaccine nationalism in developed countries is erecting insurmountable barriers to access for developing countries. Rigid intellectual property rules limit African countries’ ability to test and manufacture COVID-19 vaccines at a low cost. Consequently, when some low and middle-income African countries secure vaccine supplies, they are paying more than their counterparts in wealthy countries. South Africa paid $5.25 per dose to the Serum Institute of India for the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, more than double the $2.16 paid by EU countries.

What can be done to alleviate the situation?

Within Africa, some steps can be taken. More countries should secure supplementary deals with individual manufacturers to protect healthcare workers, policymakers, military personnel, and other sectors critical to national security. The Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s outstanding efforts in regional coordination, timely information sharing, and quality control of Chinese supplies should be maintained.

However, relying solely on COVAX and other charitable donations to combat a raging pandemic cannot be a long-term public health strategy for Africans. In order to coexist with COVID-19 in the medium run while limiting infections and deaths, the African Union should be more pragmatic in coordinating its member states’ strategies. Investments in African R&D and pharmaceutical products should indeed be made.

Wealthy countries must also take additional steps. They have a moral obligation to not intentionally deny developing countries access to medical supplies and treatments that could save billions of lives. Moreover, the WTO should make it a priority to coordinate the relaxation of intellectual property protections for COVID-19 pharmaceutical technology, allowing for more timely and affordable universal access while also strengthening the manufacturing capacity in developing countries.

Siya Kalsi

MemberClick here to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.